Desde Monterrey, Nuevo León; Mèxico.

BIENVENIDA DEL DIRECTOR

BIENVENIDA DEL DIRECTOR

Me da mucho gusto darles la bienvenida al departamento de Pediatría de la Escuela de Medicina del Tecnológico de Monterrey.

En 1983 los primero estudiantes de nuestra escuela de medicina cursaban sus primeras 12 semanas por pediatría. Desde entonces ha sido nuestro principal interés preparar a los alumnos con los conceptos básicos, que les ayuden a ser los mejores médicos generales con un profundo conocimiento de las condiciones normales, cambios fisiológicos y patologías más comunes de los niños y adolescentes.

Durante estas 12 semanas van a tener exposición a pacientes hospitalizados, desde recién nacidos en el departamento de cunas y en la unidad de terapia intensiva neonatal y pediátrica, también en el área de pediatría general los niños y adolescentes con problemas médicos y quirúrgicos. La oportunidad de tener el primer contacto con los pacientes en el departamento de emergencias pediátricas. Y poder conocer toda la variedad de enfermedades de nuestra población rotando por el Hospital Infantil de Monterrey – SSA.

Por otra parte, la gran parte del aprendizaje durante este tiempo va a suceder en ambulatorio: guardería, escuela, Abatón, consulta externa con un profesor de Pediatría.

Esperamos que aprovechen esta rotación al máximo, los profesores de pediatría son los mejores asesores, ellos están en capacitación constante y poseen los más altos valores para ser ejemplo de los estudiantes.

En el Hospital San José – Tec de Monterrey van a encontrar al personal de salud comprometido con la institución y educación de ustedes, ellos son los mejores maestros; y me refiero a las enfermeras, técnicos y residentes.

Recuerden que la niñez es el futuro de nuestra sociedad, trabajemos por un mejor futuro.

¿ POR QUÉ LLAMARLE PROPILEOS ?

Propileos en la Acrópolis Ateniense.

Cuando, durante la aurora de la humanidad, el hombre consideró que era mejor establecerse con su familia en un sólo lugar ....

PERFIL DEL ALUMNO

1) NOMBRE COMPLETO :

3) NÚMERO DE MATRÍCULA :

4) FECHA Y LUGAR DE NACIMIENTO :

5) LUGAR DE RESIDENCIA :

7) ESTADO CIVIL :

11) TELÉFONO PARA LOCALIZARLE ( casa y/o móvil ) :

14) ÁREAS MÉDICAS DE INTERÉS :

16) MATERIAS DE ESTA CARRERA QUE ADEUDA :

17) ESTUDIOS REALIZADOS ADEMÁS DE LA PREPARATORIA Y ESTA CARRERA :

18) IDIOMAS QUE DOMINA (%) :

19) DESCRIPCIÓN DE LA FAMILIA ( Nombre de cada integrante, edad, estudios, ocupaciones y lugar donde radican) :

20) OCUPACIONES FAVORITAS EXTRAACADÉMICAS :

21) LIBROS AJENOS A LA CARRERA QUE HA LEÍDO EN EL ÚLTIMO AÑO :

22) MEMBRESÍAS A SOCIEDADES :

CREA UN BLOG

ACTIVIDAD NÚMERO DOS :

.

Es importante que cada alumno cree su propio BLOG y nos haga llegar a sus maestros ( a través del Perfil del Alumno ) la dirección (URL) de éste para poder constantemente revisarlo.

El blog se utilzará para subir las MEDITACIONES y el REPORTE DE FALTAS Y RETARDOS.

Las MEDITACIONES son cortas redacciones que deberán ser el resultado de una introspección que analice

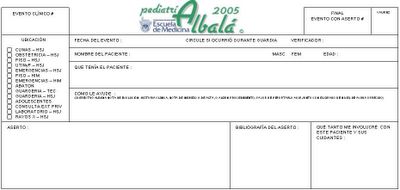

ALBALÁ

.

.

ALBALÁ :

Es un instrumento mensurador de la amplitud y profundidad de la exposición clínica de los estudiantes, que permite estandarizar y que invita al alumno a estudiar e investigar; a la vez que a los coordinadores les permite evaluar al alumno, a los profesores y a los campos clínicos.

Cada Evento Clínico vivenciado por el alumno debe quedar registrado en su Albalá.

Se define Evento Clínico como “cada vez que, ante un paciente, se ejerce el juicio clínico y/o se efectúa uno o varios procedimientos que no son parte de la exploración física de rutina”.

El alumno también describe en cada Evento Clínico, cuál fue su nivel de actuación.

Hay 5 niveles de actuación posibles :

1. Observé.

2. Ayudé.

3. Hice con Supervisión.

4. Hice sin Supervisión.

5. Supervisé.

CALENDARIO DE CLASES Y ACTIVIDADES.

Semana 1 - JULIO 2005 - lu 4, ma 5, mi 6, ju 7, vi 8, sá 9, do 10

Bienvenida. Incorporación al Equipo de Salud. Propedéutica. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Felícitos Leal.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- La importancia de la queja principal (Dr. Felícitos Leal)

- Cómo disipar la angustia y devolver la esperanza (Dr. Felícitos Leal)

- Cómo explora el experto (Dr. Felícitos Leal)

- Relevancia del hábito de documentar (Dr. Ismael Piedra)

(Sábado libre).

Semana 2 - JULIO 2005 - lu 11, ma 12, mi 13, ju 14, vi 15, sá 16, do 17

Urgencias Extremas. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Carlos Cuello García.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- Cómo es la vida del pediatra y cómo se espera que se comporte <énfasis en profesionalismo, valores y actitudes> (Dr. Carlos Zertuche)

- Practicando una pediatría basada en evidencias

(Sábado : Envenenamientos ; Profesor Encargado : Dr. Jesús Santos Guzmán.).

* EMIS A1 y B1 (Consulta Externa Dr. Uscanga) (GUARDIA Ma/Sa) : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 (Consulta Externa Dr. Rubén Darío) : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 (Consulta Externa Dr. Gilberto Garza) : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 (Consulta Externa Dr. Zertuche) (GUARDIA Ma/Sa) : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 (Consulta Externa Dr. Lozano Lee/Valencia) : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 (Consulta Externa Dra. Estrella) : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 (Consulta Externa Dr. Ricaurte) : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 (Consulta Externa Dr. Vargas) (GUARDIA Ma/Sa) : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 (Consulta Externa Dr. Ibarra) : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 (Consulta Externa Dr. Valencia) : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 (Consulta Externa Dr. Manuel Pérez) : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 (Consulta Externa Dr. Yee/Cuello) : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 (Consulta Externa Dra. Pilar Campos) : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 (Consulta Externa Dr. Amarante) : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 (Consulta Externa Dr. Jorge Torres) : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 (Consulta Externa Dr. -por definir-) : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 (Consulta Externa Dr. -por definir-) : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 (Consulta Externa Dr. -por definir-) : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 3 - JULIO 2005 - lu 18, ma 19, mi 20, ju 21, vi 22, sá 23, do 24

Problemas propios del Recién Nacido y Dismorfología. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Roberto Hernández Niño.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- La formación de un arsenal terapéutico propio (Dr. Manuel Pérez)

- El laboratorio clínico como herramienta diagnóstica en pediatría (Dr. José Antonio Lozano)

(Sábado : Rehidratación Oral y Paraenteral ; Profesor Encargado : Dr. Felícitos Leal ).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte

* EMIS A3 y B3 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A4 y B4 : EMERGENCIA

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : PISO HSJ 1a parte

* EMIS A7 y B7 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. patre

* EMIS C2 y D2 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte

* EMIS C3 y D3 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C4 y D4 : EMERGENCIA

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : PISO HSJ 1a parte

* EMIS C7 y D7 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C10 y D10 : CUNERO HSJ

Semana 4 - JULIO 2005 - lu 25, ma 26, mi 27, ju 28, vi 29, sá 30, do 31

Crecimiento y Nutrición. Profesor Encargado. : Dr. Francisco Lozano Lee.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- El arte de prescribir y el arte de aconsejar (Dr. Felícitos Leal)

- Cómo evitar yatrogenias (Dr. Felícitos Leal)

- En defensa de los niños (Dr. Manuel Ochoa)

VIERNES 08:00 : PRIMER EXAMEN ESCRITO (semana 1 a 3)

Profesor Encargado : Dr. Carlos Cuello

(Sábado libre).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 5 - AGOSTO 2005 - lu 1, ma 2, mi 3, ju 4 , vi 5, sá 6, do 7

Desarrollo y Comportamiento. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Manuel Pérez Jiménez.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- EURICLEA: Conocer para poder Reconocer

- Problemas hematológicos comunes (Dr. Óscar González)

(Sábado : Problemas propios de los Adolescentes ; Profesor Encargado : Dr. Ricardo Noriega González).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 6 - AGOSTO 2005 - lu 8, ma 9, mi 10, ju 11 , vi 12, sá 13, do 14

Supervisión de la Salud y Prevención de Lesiones. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Jesús Ibarra Jiménez.

(Sábado : libre).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 7 - AGOSTO 2005 - lu 15, ma 16, mi 17, ju 18 , vi 19, sá 20, do 21

Enfermedades Prevenibles e Inmunizaciones. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Héctor Yee.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- Conceptos básicos de paidología (Dr. Héctor Yee)

(Miércoles 13:00 a 15:00 hrs. : Retroalimentación de mitad de curso - TODOS los alumnos, profesores y residentes están invitados).

VIERNES 08:00 : SEGUNDO EXAMEN ESCRITO (semana 1 a 6)

Profesor Encargado: Dr. Felícitos Leal

---Viernes Noche : TERTULIA de EMIS, Residentes y Maestros---

***La organizan los EMIS con la asesoría de los Dres. Manuel Pérez, Ismael Piedra y nuestro Jefe de Residentes ***

(los EMIS que tengan guardia este día, pueden abandonar el hospital a las 22:00 hrs.).

(Sábado: Profesionalismo : Sesión de Ética a través del Curriculum , Profesor Encargado : Dra. Claudia Hernández. Liga : http://dcs.mty.itesm.mx/profesionalismo/sesionescc.html).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 8 - AGOSTO 2005 - lu 22, ma 23, mi 24, ju 25 , vi 26, sá 27, do 28

Temas Selectos de Otorrinolaringología. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Felícitos Leal.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- El significado de la fiebre (Dr. Felícitos Leal)

- Ayudando a morir (Dr. Roberto Hernández Niño)

(Sábado : - Problemas comunes en ortopedia ( Dr. )).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 9 - AGOSTO / SEPT 2005 - lu 29, ma 30, mi 31, ju 1 , vi 2, sá 3, do 4

Temas Selectos de Neumología y Cardiología. Profesores Encargados : Drs. Carlos Cuello García y Jesús Manuel Yáñez.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- La radiología como herramienta diagnóstica en pediatría (Dra. Yolanda Tejada)

VIERNES 08:00 : TERCER EXAMEN ESCRITO (semana 1 a 8)

Profesor Encargado : Dr. Felícitos Leal

(Sábado : - Evaluación preoperatoria, analgesia y sedación (Dr. Abelardo García Cantú) ).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 10 - SEPTIEMBRE 2005 - lu 5, ma 6, mi 7, ju 8 , vi 9, sá 10, do 11

Temas Selectos de Gastroenterología. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Rubén Darío Rodríguez Muñoz.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- Cuándo llevar a un niño a cirugía (Dr. Salvador Villarreal)

(Sábado : libre).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 11 - SEPTIEMBRE 2005 - lu 12, ma 13, mi 14, ju 15 , vi 16, sá 17, do 18

Temas Selectos de Alergología. Profesor Encargado : Dr. Oscar Valencia Urrea.

CONFERENCIAS MAGISTRALES DE LA SEMANA :

- Problemas neurológicos comunes (Dr. Arturo Garza Peña).

VIERNES 08:00 : CUARTO EXAMEN ESCRITO (semana 1 a 11, sí : once)

Profesor Encargado : Dr. Carlos Cuello

(Sábado : libre).

* EMIS A1 y B1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. patre

* EMIS A2 y B2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A3 y B3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS A4 y B4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS A5 y B5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS A6 y B6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS A7 y B7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A8 y B8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS A9 y B9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS A 10 y B10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

* EMIS C1 y D1 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 1a. parte.

* EMIS C2 y D2 : PISO HSJ 3a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C3 y D3 : EMERGENCIAS HSJ

* EMIS C4 y D4 : PISO HSJ 2a. parte

* EMIS C5 y D5 : PISO HSJ 1a. parte

* EMIS C6 y D6 : ADOLESCENTES

* EMIS C7 y D7 : GUARDERÍA 2a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C8 y D8 : GUARDERÍA 1a. parte / ABATÓN

* EMIS C9 y D9 : CUNERO HSJ

* EMIS C 10 y D10 : HOSPITAL INFANTIL DE MTY. 2a. parte

Semana 12 - SEPTIEMBRE 2005 - lu 19, ma 20, mi 21, ju 22 , vi 23, sá 24, do 25

EVALUACIONES FINALES (TODO EL MATERIAL)

<Exámenes Orales ante el Consejo Académico de Pediatría>

vale 35% de la calificación final de PEDIATRÍA TEÓRICA.

Retroalimentación de final de curso - TODOS los alumnos, profesores y residentes están invitados).

FIN DEL CURSO.

--- Las Calificaciones aparecerán en el Blog de Evaluaciones

(http://pediatria-itesm.blogspot.com)

10 días naturales después del viernes de la semana 12 (un lunes).---

QUÉ DEBERÁ SER CAPAZ DE SABER

( como médico general )

DE LOS SIGUIENTES TEMAS

2) Sepsis / Falla Multiorgánica

3) Envenenamientos (Incluye Intoxicación por Plomo)

4) Supervisión de la Salud y Tamizaciones.

5) Malnutrición (desnutrición, anemia ferropénica, obesidad, anorexia nervosa, bulimia).

6) Manejo del Paciente Policontundido (Traumatismo Craneoencefálico, Trauma Espinal, Trauma Abdominal, Trauma Ortopédico).

7) Sedación y Control del Dolor.

8) Transportación Terrestre y Aérea del Paciente Pediátrico.

9) Prevención de Lesiones.

10) Síndrome Diarreico Agudo.

11) Diagnóstico y Manejo del Niño con Dificultad Respiratoria.

12) Asma.

13) Infecciones de la vía respiratoria alta (catarro común, otitis media aguda, otitis media crónica, otitis externa, sinusitis, faringoamigdalitis).

14) Adicciones (tabaco, etanol, inhalados, drogas de la calle o de los clubs).

15) Sexualidad / Embarazo en la Adolescencia.

16) Depresión / Suicidio.

17) Lactancia.

18) Inmunizaciones.

19) Abuso Infantil.

20) Deshidratación (Incluye Choque Hipovolémico).

21) Atención Perinatal del Paciente Pediátrico.

22) Manejo del Niño con Fiebre.

23) Manejo del Niño y Adolescente con Problemas de Conducta.

DE LOS SIGUIENTES TEMAS

2) Dermatitis atópica.

3) Bronquiolitis viral.

4) Laringotraqueobronquitis viral.

5) Croup espasmódico.

6) Alergia a las proteínas de la leche.

7) Alergia a alimentos.

8) Infección de Vías Urinarias.

9) Reflujo Vésicoureteral.

10) Bacteriemia / Sepsis.

11) Meningitis viral.

12) Meningitis bacteriana.

13) Meningitis tuberculosa.

14) Tuberculosis pulmonar.

15) Neumonía bacteriana.

16) Neumonía viral.

17) Neumonía por micoplasma pneumoniae.

18) Reflujo Gastroesofágico.

19) Leucemia Linfoblástica Aguda.

20) Anafilaxis.

21) Angioedema.

22) Urticaria.

23) Mordedura de Humanos y de Animales.

24) Apendicitis.

25) Artritis Reumatoide Juvenil.

26) Déficit de la Atención / Hiperactividad.

27) Cólico del Lactante.

28) Conjuntivitis.

29) Constipación / Encopresis.

30) Enuresis.

31) Anticoncepción.

32) Laringotraqueobronquitis Viral.

33) Criptorquidia.

34) Trastornos del Desarrollo.

35) Displasia del Desarrollo de la Cadera.

36) Diabetes Mellitus.

37) Eritema en el Área del Pañal.

38) Síndrome Down (Trisomía 21)

39) Mononucleosis Infecciosa.

40) Intoxicación Alimentaria.

41) Infección de la Piel por Hongos.

42) Gastritis.

43) Reflujo Gastroesofágico.

44) Enfermedad Mano-Boca-Pie

45) Cefalea.

46) Impétigo.

47) Infección por Influenza.

48) Intususcepción.

49) Pediculosis.

50) Malaria.

51) Retraso Mental.

52) Parálisis Cerebral Infantil.

53) Casi Ahogamiento.

54) EL NIÑO CON MASA EN CUELLO.

55) EL NEONATO CON APNEA.

56) Síndrome Nefrótico.

57) Defectos del Tubo Neural.

58) EL NIÑO CON EPISTAXIS NASAL.

59) Osteomielitis.

60) Sarampión.

61) Eritema Infeccioso.

62) Exantema Súbito.

63) Enfermedad por Estreptococo del Grupo A / Escarlatina

64) Pertusis.

65) Difteria.

66) Infestación por Enterobius vermicularis.

67) Escabiasis.

68) Escoliosis.

69) Xifosis.

70) Dermatitis Seborreica.

71) Convulsiones Febriles.

72) Crisis Convulsivas.

73) Artritis Séptica.

74) Síndrome de Apnea Obstructiva durante el Sueño.

75) Síndrome de Muerte Súbita / Muerte Súbita Fallida (ALTE).

76) Sinovitis Transitoria.

77) Infestación por Cestodos.

78) Diarrea del Lactante.

79) Taquipnea Transitoria del Recién Nacido.

80) Triquinosis.

81) Leucorrea

82) Vaginitis.

83) Hepatitis Viral.

84) Infección por Virus Sincitial Respiratorio.

85) Verrugas.

86) Varicela.

87) EL NIÑO CON LLANTO EXCESIVO.

88) EL NIÑO CON TRASTORNOS DEL SUEÑO.

89) Higiene Oral.

90) Caries.

91) Trauma Dental.

92) Dermatitis del Pañal.

93) Acné.

94) Tinea Capitis.

95) Tinea Corporis.

96) SUTURA DE HERIDAS MENORES.

97) EL NIÑO QUEMADO.

98) EL NIÑO CON DOLOR CRÓNICO.

99) EL NIÑO CON RETRASO EN EL DESARROLLO.

100) EL NIÑO CON FALLA ESCOLAR Y TRASTORNOS DEL APRENDIZAJE.

101) EL NIÑO QUE COJEA.

102) EL NIÑO CIANÓTICO.

103) EL NIÑO ACIDÓTICO.

104) EL NIÑO CON DOLOR TORÁCICO.

105) EL NIÑO CON HEMATOQUESIA.

106) EL NIÑO ANÉMICO.

107) EL NIÑO EN COMA.

108) EL NIÑO CON DOLOR ABDOMINAL.

109) EL NIÑO CON DOLOR ESCROTAL AGUDO.

110) Torsión de Cordón Espermático (Testicular) / Torsión de Hidátide.

111) Circuncisión.

112) Adherencia de Labios Menores.

113) EL NIÑO CON TOS Y FIEBRE.

114) EL NIÑO QUE VOMITA.

115) EL NIÑO CON SOPLO CARDIACO.

116) EL NIÑO CON RETRASO EN EL HABLA.

117) Linfadenopatía.

DE LOS SIGUIENTES TEMAS

2) Deficiencia de Alfa -1- Antitripsina.

3) Ambliopía.

4) Infección por Anaerobios.

5) Anemia por Enfermedad Crónica.

6) Estenosis de la Válvula Aórtica.

7) Apnea del Prematuro.

8) Infestación por Áscaris Lumbricoides.

9) Asplenia / Hiposplenia.

10) Ataxia.

11) Atelectasia.

12) Comunicación Interauricular.

13) Infección por Micobacteria Atípica.

14) Trastornos Autísticos.

15) Anemia Hemolítica Autoinmune.

16) Necrosis Avascular de la Cabeza del Fémur.

17) Balanitis.

18) Atresia de las Vías Biliares.

19) Blefaritis.

20) Transplante de Médula Ósea.

21) Botulismo.

22) Absceso Cerebral.

23) Tumor Cerebral.

24) Fístula Branquial.

25) Absceso Mamario en el Recién Nacido.

26) Ictericia por Seno Materno y por Leche Materna.

27) Espasmo del Sollozo.

28) Displasia Broncopulmonar.

29) Brucelosis.

30) Infección por Campilobacter.

31) Candidiasis.

32) Cataratas.

33) Cardiomiopatías.

34) Enfermedad por Arañazo de Gato.

35) Enfermedad Celíaca.

36) Celulitis.

37) Parálisis Infantil.

38) Neumonía por Clamidia.

39) Labio / Paladar hendido.

40) Pie Equinovaro.

41) Coartación de la Aorta.

42) Hipotiroidismo Congénito.

43) Falla Cardíaca Congestiva.

44) Dermatitis de Contacto.

45) Cor Pulmonale.

46) Costocondritis.

47) Enfermedad de Crohn.

48) Fibrosis Quística del Páncreas.

49) Infección por Citomegalovirus.

50) Complejo Dermatomiositis / Polimiositis.

51) Diabetes Insípida.

52) Cetoacidosis Diabética.

53) Hernia Diafragmática Congénita.

54) Síndrome DiGeorge.

55) Disquitis.

56) Coagulación Intravascular Diseminada.

57) Sangrado Uterino Disfuncional.

58) Dismenorrea.

59) Encephalitis.

60) Endocarditis.

61) Neumonía Eosinofílica.

62) Epiglotitis.

63) Eritema Multiforme.

64) Eritema Nodoso.

65) Sarcoma de Ewing.

66) Síndrome del Niño Fláccido.

67) Giardiasis.

68) Gingivitis.

69) Glaucoma Congénito.

70) Glomérulonefritis.

71) Deficiencia de Glucosa 6 Fosfato Deshidrogenasa.

72) Bocio.

73) Infección por Gonococo.

74) Enfermedad de Graves.

75) Deficiencia de Hormona de Crecimiento.

76) Síndrome Guillan-Barré.

77) Ginecomastia.

78) Golpe de Calor (Insolación).

79) Hemangioma.

80) Enfermedad Hemolítica del Recién Nacido.

81) Síndrome Urémico-Hemolítico.

82) Hemofilia.

83) Hemoptisis.

84) Púrpura de Henoch-Scönlein

85) Esferocitosis Hereditaria.

86) Infección por el Virus del Herpes Simple.

87) Hipo.

88) Enfermedad de Hirschprung.

89) Histoplasmosis.

90) Linfoma de Hodgkin.

91) Virus de la Inmunodeficiencia Humana.

92) Hidrocefalia.

93) Hidronefrosis.

94) Hiperinsulinismo / Hipoglicemia.

95) Molusco Contagioso.

96) Pitiriasis rosada.

97) Hemangiomas.

98) Varicocele.

99) Enfermedad por Yersinia enterocolitica.

100) Hiperlipidemia.

101) Hipertensión.

102) Púrpura Idiopática Trombocitopénica.

103) Inmunodeficiencia.

104) Deficiencia de Inmunoglobulina A.

105) Ano Imperforado.

106) Secreción Inapropiada de Hormona Antidiurética.

107) Anteversión Femoral Aumentada.

108) Espasmos Infantiles.

109) Hernia Inguinal.

110) Reacción a la picadura de Insectos.

111) Obstrucción Intestinal.

112) Hemorragia Intracraneal.

113) Síndrome de Intestino Irritable.

114) Enfermedad de Kawasaki.

115) Obstrucción del Ducto Lacrimal.

116) Intolerancia a la lactosa.

117) Intoxicación por plomo.

118) Enfermedad de Lyme.

119) Mastoiditis.

120) Conducto Arterioso Patente.

121) Divertículo de Meckel.

122) Meningococcemia.

123) Adenitis Mesentérica.

124) Errores Innatos del Metabolismo.

125) Enfermedades Metabólicas con Disfunción Hepática.

126) Enfermedades Metabólicas con Disfunción Neurológica.

127) Milia.

128) Alergia a las Proteínas de la Leche.

129) Parotiditis.

130) Síndrome Munchausen por Poder.

131) Distrofias Musculares.

132) Miocarditis.

133) Enterocolitis Necrozante.

134) Neuroblastoma.

135) Neutropenia.

136) Linfoma No Hodgkin.

137) Osteogénesis Imperfecta.

138) Osteosarcoma.

139) Pseudoquiste Pancreático.

140) Pancreatitis.

141) Enfermedad Inflamatoria Pélvica.

142) Pericarditis.

143) Respiración Periódica.

144) Celulitis Periorbitaria.

145) Celulitis Retroseptal.

146) Peritonitis.

147) Absceso Retrofaríngeo.

148) Hipertensión Pulmonar Persistente del Recién Nacido.

149) Enfermedad de Legg-Calve-Perthes.

150) Fotosensibilidad.

151) Infección por Pneumocystis carinii.

152) Neumotórax.

153) Enfermedad Poliquística del Riñón.

154) Síndrome de Ovario Poliquístico.

155) Policitemia.

156) Displasia de la Corteza a Cerbral

157) Hipertensión Portal.

158) Valvas Uretrales Posteriores.

159) Adrenarquia Prematura.

160) Telarquia Prematura.

161) Síndrome Premenstrual.

162) Síndrome del Intervalo QT prolongado.

163) Síndrome de Prune-Belly.

164) Pseudotumor Cerebri.

165) Psoriasis.

166) Retraso de la Pubertad.

167) Hipertensión Pulmonar.

168) Estenosis de la Válvula Pulmonar.

169) Nefronía / Pielonefritis.

170) Estenosis Pilórica.

171) Rabia.

172) Prolapso Rectal.

173) Insuficiencia Renal Aguda.

174) Insuficiencia Renal Crónica.

175) Acidosis Tubular Renal.

176) Trombosis de la Vena Renal.

177) Tumor de Wilms.

178) Retinoblastoma.

179) Síndrome de Reye.

180) Fiebre Reumática.

181) Raquitismo.

182) Riquetsiosis.

183) Fiebre de las Montañas Rocallosas.

184) Salmonelosis.

185) Enfermedad del Suero.

186) Inmunodeficiencia Combinada Severa.

187) Ambigüedad Sexual.

188) Precocidad Sexual.

189) Síndrome de Intestino Corto.

190) Anemia de Células Falciformes.

191) Deslizamiento de la Cabeza del Fémur.

192) Atrofia Espino-Medular.

193) Síndrome de la Piel Escaldada por Estafilococo.

194) Status Epilepticus.

195) Síndrome de Stevens-Johnson.

196) Estomatitis.

197) Estrabismo.

198) Tartamudez.

199) Hematoma Subdural.

200) Taquicardia Supraventricular.

201) Síncope.

202) Sífilis.

203) Teratoma.

204) Tétanos.

205) Tetralogía de Fallot.

206) Talasemia.

207) Torsión Tibial.

208) Fiebre por Garrapata.

209) Tics.

210) Síndrome de Shock Tóxico.

211) Toxoplasmosis.

212) Traqueitis Bacteriana.

213) Fístula Traqueoesofágica.

214) Reacción por Transfusión.

215) Eritroblastopenia Transitoria de la Infancia.

216) Traqueomalacia / Laringomalacia.

217) Transposición de los Grandes Vasos.

218) Colitis Ulcerativa.

219) Comunicación Interventricular.

220) Taquicardia Ventricular.

221) Vólvulus.

222) Enfermedad de Von Willebrand.

223) Enfermedad de Wilson.

224) Síndrome de Wiskott- Aldrich.

225) Enfermedad por de Wiskott- Aldrich.

226) Hiperplasia Adrenal Congénita.

Gráficas Somatométricas según la CDC, año 2000.

¡ ESCUCHE "AVANCES EN PEDIATRÍA" !

.

SEMANA 1 ( LECTURA C ) The New Morbidity Revisited: A Renewed Commitment to the

http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/reprint/pediatrics;108/5/1227.pdf

SEMANA 1 ( LECTURA D ) The Pediatric History

William E. Boyle, Jr., Robert A. Hoekelman

"A good history carefully obtained from an intelligent mother ... puts the physician in possession of a fund of information about the patient which is of greatest value, not only in arriving at a diagnosis in the illness for which he is consulted, but is exceedingly helpful in the future management of the child."

L. Emmett Holt, 1908 1

A history is a narrative related by the patient or his family. It is a unique story in which are embedded the words, phrases, and clues that will direct the physician to the general or specific medical problem of the patient. It requires the physician to pay close attention to this detailed sequence of events, and through careful direct questioning formulate a differential diagnosis. Parents and patients hope the physician will hear their story and interpret it correctly. It in not an easy task.

Perhaps in no other medical field is a history as important as it is in pediatrics. For early detection of problems related to health (including growth, development, and nutrition) and for prevention of future difficulties, the practitioner must have a thorough knowledge of the child and the family, their lifestyle, and their environment. Unlike in most other areas of medicine, the pediatric history usually is given by someone other than the patient. Thus, a certain amount of subjectivity and objectivity is lost. Signs and symptoms are filtered through parental perspectives before emerging as historical data and, therefore, are influenced by parental hopes and fears. A pediatric history is a compilation of information gathered in a variety of ways—through interviews, direct observations, questionnaires, and medical records—that usually provides a concise record of the child and the family.

In the past, training in interviewing and history taking took place for an acute problem in which the concern or complaint was readily stated or easily seen. Today, however, children are treated for an increasing number of psychosocial problems, usually as outpatients. These may include learning difficulties, chronic or disabling conditions, or behavioral or developmental problems—all of which require sensitive, insightful listening. Thus, the pediatrician must have a thorough knowledge of the child's health status, developmental stage, and cognitive level, as well as the family's functional characteristics, belief systems, and socioeconomic circumstances. Much of pediatrics has to do with vague questions or concerns, such as "Why does she cry so much?" "Why is he so thin?" or "Is that cough serious?" These concerns must be answered and expectations dealt with if the encounter is to be fruitful. If the physician and parent or patient have different perceptions of the problem, the physician must attempt to "tease out" and understand the patient's or parent's concerns.

Much transpires during the initial interview between a practitioner and a family other than the gathering of a history. The tone of all future encounters is established, and ideally the family begins to develop a trusting, confident relationship with the practitioner. Just as the practitioner is trying to assess the problem at hand, so, too, are the parents (and child) "sizing up" the clinician and trying to feel comfortable with him or her. A warm, friendly, nonjudgmental, courteous manner certainly facilitates this. History taking requires some degree of decision making on the part of the interviewer as to what is relevant. It is not merely the gathering of a list of all symptoms and pertinent historical "negatives"; it also involves the synthesis of various facts, attitudes, and observations. To do this well requires experience, tact, and some degree of intuition. It is a difficult task. A history is compiled best if, for each visit, the practitioner can obtain the answers to three questions: "Why did you come today?"; "What are you worried about most?"; and "Why does that worry you?" The answers not only direct further inquiry but also provide clues to parent and patient concerns that need to be allayed or dealt with directly during the visit and, perhaps, thereafter. For example, a parent who brings a child to a physician because of swollen cervical lymph nodes may be worried that they represent the first signs of malignancy, because an aunt who died of Hodgkin's disease had the same problem. Parents, older children, and adolescents need to be told what symptoms and signs do not represent, as well as what they do represent, especially if the parents and patient are worried that the symptoms and signs indicate a serious or fatal illness.

SETTING AND AMBIANCE

Clothing and appearance may affect the ease with which a relationship is established. Parents and children view a visit to the pediatrician as a special occasion and frequently dress accordingly. They hope their practitioner will view the visit in the same manner. The practitioner's dress should be appropriate to the population served and consistent with local values. Most pediatricians do not wear a white coat because it may evoke fearful memories for the child, although this has never been substantiated. Whatever the attire, a sense of competence must be conveyed.

TYPES OF INTERVIEWS

This chapter focuses on the information to be gathered and the techniques used in obtaining the comprehensive pediatric history, which usually is accomplished in a single sitting. Circumstances may preclude completion of this exercise during the initial visit, however, and much of the information will have to be gathered at subsequent visits. For example, the initial history obtained for a child who has acute otitis media and who is "squeezed in" during fully scheduled office hours will be brief and related primarily to the chief complaint. The rest of the history can be obtained during a scheduled follow-up visit when adequate time is allotted for this purpose.

Prenatal Interview

Ideally, the person who has cared for the woman throughout her pregnancy and delivery and who understands her needs should be the person who will help her understand her new role as a mother. In many communities this is not done. Obstetricians traditionally care for women only throughout pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period. Pediatricians traditionally assume care of the infant at birth. Many women find it difficult to leave someone who has supported them through a difficult psychobiological change and to develop a new relationship while they learn the new role of motherhood. Thus, a prenatal interview can greatly assist in this transition.

Prenatal interviews do not need to be long or detailed; 20 to 30 minutes should suffice. In addition to gathering facts, the pediatrician should set a tone for future encounters. Husband and wife should be interviewed together, if possible, so that parental concerns can be aired and they can be helped to support each other. All parents are anxious about their adequacy and the health of their unborn infant, and a supportive attitude and tacit acknowledgment that these fears are understandable can be most helpful.

Taking a thorough family history is one way of evidencing concern, not just for the child but for the entire family. Parents should understand the physician's interest in them as individuals and not merely as Teddy's or Sarah Jane's mother and father.

During a typical prenatal interview, plans for labor and delivery should be discussed, as well as a program of childbirth education and the type of infant feeding that is contemplated. It is wise at this time to point out certain safety issues to which the parents should attend before their baby comes home, such as obtaining a child safety seat and a smoke detector and setting the hot water heater at a safe temperature (see Chapter 23 [Two], Injury Control). Circumcision should be discussed, unless the couple has learned through tests that their baby is a girl. It also is helpful to point out to the parents that they obviously have imagined a variety of circumstances for their child, which the clinician can understand and help with if they arise. It should be noted whether one or both parents desire a child of a particular gender, which may affect their abilities as parents.

The mother's blood type, medications taken, and rubella status (if known) should be elicited. Genetic information should be gathered about both sets of grandparents. In addition to inherited disorders and birth defects, familial tendencies such as obesity, hypertension, and short stature should be investigated. It also is wise to ask what the couple's own parents were like, because parenting techniques and styles frequently are passed from one generation to the next.

After dealing with the family history, the clinician needs to gather some information about other supportive individuals. Who will help out when the baby comes home? Will the husband have a paternity leave of some sort? Grandparents traditionally visit shortly after delivery, and the pediatrician should point this out and ask if they will be helpful or another burden. He or she also should inquire if transportation and a telephone are readily available. The physician should be alert at all times for evidence of undue stress, isolation, and prior deprivation because these factors are known to be predictors of poor parenting. The parents will want to know when the pediatrician will see the baby in the hospital, what the appointment schedule will be, and how the pediatrician can be reached. Fees for visits also can be discussed at this time.

The parents should be allowed to ask questions about their concerns. It is best to support their instincts rather than to direct and show one's own personal bias. The pediatrician should anticipate certain normal variations such as sleepy babies, the postpartum "blues," and the physiological slump that lasts from 6 to 8 weeks after birth. Parental questions may seem trivial (skin care, type of diapers), but all evolve around the question, "Will we be good parents?" Strong reassurance that their instincts are good serves to reinforce and strengthen the couple's tendencies toward good parenting and leads to a confident beginning as parents.

At the conclusion of the interview the practitioner should have an idea of the parents' lifestyle and coping mechanisms, and they should feel reassured that they have a supportive person who will help them enter parenthood.

As prenatal interviewing has become more widespread, interview requests for second or subsequent pregnancies have become more common. These generally are not quite so formal and can take place during the routine health maintenance visits of an older child. Parental concerns deal not only with the health and soundness of the unborn, but also with coping with another child. "Will I be able to divide myself and still survive?" The mother finds herself torn between her baby in utero and her baby at home, and this issue must be addressed. Inappropriately, she may have her child attempt new developmental tasks such as toilet-training so that in essence she will have only one baby. She also may force a child to "grow up" and relinquish a crib, stroller, or high chair. All these efforts should be discouraged. Separation at the time of delivery can be a problem for a child, who must be told that mommy will leave for a while and then return. This should be done shortly before the expected confinement. The mother's departure can be made easier by having the child help the mother pack for her hospital stay. The separation also will stress the supports the family has developed, and the clinician should review these at this time. It, likewise, is important to recount the previous birth experience, so that conflicts or problems may be identified and, thus, avoided a second time. The mother should be reassured that she will be able to cope and that support will be available.

Comprehensive Pediatric History Interview

Box 7-1 is a suggested outline for components of a comprehensive pediatric history. In certain settings some of the data already will have been gathered, but a thorough knowledge of each component of the history is essential. Obviously, under certain circumstances it may be necessary to gather other information; the boxed material merely suggests a general format.

Usually the interview begins with the parents stating the concerns that led to the present encounter—the chief complaint. The parents should then be allowed, with as little interruption as possible, to relate the history as they recall it. Certain areas may be amplified and clarified, but direct or challenging questions should be avoided. After eliciting the chief complaint, the practitioner should enumerate the events associated with it in an orderly sequence (present illness). In addition to facts, parental concerns and feelings about these symptoms should be elicited. The parents should be asked to speculate on what they think is causing the complaint or symptom. This information can be valuable in several respects. First, it demonstrates the level of parental concern, which may influence subsequent care and treatment. Thus, parents who equate nosebleeds with leukemia, for instance, will need more than simple reassurance. Second, parental concerns about causation may "color" the history a great deal; for example, their concern about developmental delay can influence the information they supply about achievement of early milestones. It always is important to discover how the present illness affects the rest of the family. This information will help the physician better understand the family's concerns about and responses to a given symptom or illness and what, if any, secondary gain exists for the child.

Although the chief complaint must remain the central focus of the interview, it frequently is obvious that it is not the main problem. This especially is true when dealing with very young children. Tired, anxious, or frightened parents often perceive their reactions to an infant as being abnormal in some way; they then project this as something being wrong with the baby. This makes seeking help acceptable. Once the practitioner recognizes this, he or she should try to create an atmosphere that allows the parents to express all their concerns. Questions such as, "Are there any other problems with Kathy you would like to discuss?" or "Is there anything else bothering you about Connor?" might facilitate communication.

After the present illness has been defined and elaborated upon, certain significant events should be enumerated (past medical history). Much of this material is factual and can be obtained by using a direct question and answer format. Significant events such as operations, serious injuries, and hospitalizations should be verified by obtaining and reviewing appropriate hospital records.

When obtaining the patient's early history, the practitioner should elicit medically significant facts from conception to the onset of the present illness. All areas delineated in Box 7-1 should be touched on to some degree. The amount of information obtained may vary, but prenatal problems such as bleeding, eclampsia, or infection should be noted, and birth weight, type of delivery, and neonatal problems, if any, must be described. Information about nutrition can reveal a great deal about family dynamics and parental perceptions and expectations. "Tell me how Jennifer eats" frequently brings forth a torrent of information, but its value, nutritionally speaking, may be limited. "Good eaters" and "picky eaters" frequently weigh the same, and those who "hardly eat a thing" often are overweight.

In dealing with issues of development, it frequently is best to ask an indirect question, such as "Tell me what Ann did during her first (or second) year." This usually elicits much more information than do direct questions about motor milestones. The clinician should seek information concerning the level of skill rather than the age of achievement; for example, it is more important to know that the child could make simple wants known at age 2 years than the age when the first word was uttered. Some information about social adaptability and temperament should be obtained (see Chapters 79, Interviewing Children, and 105, Interviewing Adolescents).

Previous health care is important, and the child's immunization status is a significant part of the early history. The practitioner should record all immunizations, skin tests, and pertinent screening information on a separate sheet that is readily accessible and retrievable. Filling out a few history forms later for camp or entry into preschool will prove the value of this record.

Allergies and allergic reactions also are an important part of the early history. Specific allergic reactions should be described in as much detail as possible to clarify the reaction. For example, ampicillin can cause a variety of cutaneous and gastrointestinal reactions, but only urticaria and anaphylaxis are true allergic responses to the medication. Idiosyncratic reactions to drugs such as phenothiazides also should be described.

The family history contains variable information but often is difficult to construct. An attempt should be made to trace back at least two generations on each side of the family, and any data obtained should be recorded appropriately. Fig. 7-1 shows one method of recording such data. The names, birth dates, and health of the three generations concerned usually are listed below the pedigree (although not shown here), using a number indicating each person. As more data such as births, deaths, and disease become available, they can be added easily.

Consanguinity of parents should be investigated specifically by asking if the parents are related by blood. In addition to seeking known inherited diseases such as diabetes, hemophilia, or neuromuscular disorders, the clinician should note familial tendencies such as obesity, short stature, early heart disease, and hypertension. Sometimes it is appropriate to inquire about the parenting techniques of forebears. It has been shown that abusive parents frequently were deprived or abused as children. It also is important to ask specifically about the health of the parents' brothers or sisters, because they often are overlooked during an interview.

The psychosocial history describes the child in his or her present milieu and relationships with family, peers, school, and community. This should include information about the physical setting (e.g., housing), environment, and degree of isolation. Determining how children spend the day, who cares for them, what they like to do, and what their hobbies are is important. Inquiry should be made about the support system within the family; for example, the nature of an extended family, supportive or conflicting roles, the elements of stress that exist for this child, and how the child and family cope with them.

The psychosocial history also should touch on the parents' attitudes toward discipline and expectations about achievement. When appropriate, the practitioner should determine how the parents compare this child to his or her siblings or to other children. It also is appropriate at this time to ask the parents to describe the child's temperament (e.g., "mellow," "feisty," "lazy"), as well as what they see as his or her strengths.

The review of systems should be detailed to obtain a baseline evaluation of all systems and their level of function. Children change over time, and various systems may be the target of stress or disease processes. Therefore, the clinician should reassess all organ systems periodically and record their apparent level of function.

Box 7-1

COMPREHENSIVE PEDIATRIC HISTORY

The following comprehensive pediatric history is exhaustive and obviously not meant to be used in its entirety with all patients. However, depending on the patient's age and gender and the nature of the chief complaint and the present illness, the interviewer will need to explore in depth some or all of the subjects listed. In most instances, common sense must be used in deciding how much information should be gathered.

Date of Interview

Source of and Reason for Referral

Chief Complaints

Present Illness

Past Medical History

BIRTH HISTORY

PRENATAL HISTORY

NATAL HISTORY

NEONATAL HISTORY

Feeding history

INFANCY

CHILDHOOD

Growth and development history

PHYSICAL GROWTH

DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONES

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Childhood illness

Immunizations

Screening procedures

Operations, injuries, and hospitalizations

Allergies

Current medications

Family history

Psychosocial history

Review of Systems

INTERVIEWING TECHNIQUES

Although most interviews are direct and straightforward, difficulties occasionally are encountered. Certain pitfalls can be avoided by changing the interview format or adapting particular strategies. Clarification of certain terms always is essential. For example, diarrhea and flu mean different things to different people, and no true communication can occur until such terms are defined. The temporal nature of complaints also must be assessed carefully. Children who are "always sick" may have recurrent infections that clear in 5 to 7 days, or they may have a perpetually runny nose, which is so in some children who have allergies. If the patient has been seen before, the clinician should review the child's medical record before the visit to refresh his or her memory on past health and illnesses that may relate to the reason for the current visit. Consultants should review the letter of referral and the reason for and goals of the visit before interviewing the parents and patient. Many parents see their skills as parents being challenged during the pediatric interview: "After all, if we did things right, we wouldn't need to see the doctor." They become defensive and may answer questions "ideally." At the same time, they want to share fears and worries with a caring, empathetic practitioner. The pediatrician must strive to develop this trusting relationship. By being facilitative, he or she enables the parents to ventilate fears and frustrations and sort out thoughts. Statements such as "That must have worried you" or "I bet that's upsetting" let parents know that the clinician is concerned with much more than the facts in the interview. On the other hand, statements or questions suggesting that the parents have not managed their child's illness properly, such as "You should have brought Gretchen in sooner," or "It would have been better not to have fed Stephanie," or "Why did you do that?" always should be avoided. The techniques used to obtain a complete and accurate history vary with the situation and the person being interviewed.

Types of Questions

In emergencies, the clinician should ask only direct questions (non-open-ended) that quickly elicit the important facts needed to make decisions regarding treatment. In nonemergencies, in which time is not a factor, direct questions should be used to obtain identifying data and information about pregnancy, birth, growth and development, feeding, immunizations, screening tests, previous illnesses, injuries and hospitalizations, family history, and review of systems. Direct questions should be asked one at a time. Rapid-order direct questions, such as "Has Karl ever had eczema, hay fever, asthma, or allergic reactions to drugs?" are logical to the questioner but are likely to confuse the respondent and lead to an overall "no" answer when a "yes" would be appropriate for one or more of the elements of the question. Indirect (open-ended) questions are extremely useful in eliciting the present illness and psychosocial history. The answers to open-ended questions, such as "How does Bonnie spend a typical day?", often provide clues to underlying, unstated problems and cues for pursuing specific elements of the patient's illness. However, use of open-ended questions may have to be curtailed because of time limitations, parental verbosity, or the parents' inability to focus on the information sought. Direct questions also are important in eliciting the details of the present illness and the psychosocial history. For example, if a cough is mentioned as a symptom in the patient's illness, the following sequence of direct questions is appropriate: "How long has Kathy had the cough?"; "When does she have it?"; "Does it wake her up at night?"; "What does it sound like?"; "Does she cough up any phlegm?"; "How much?"; "What does it look like?" Thus, open-ended questions identify the direction for further inquiry, and direct questions help to determine the importance of the symptoms or signs identified. Leading direct questions—for example, "Does Jane do well in school?"—should be avoided because they are more likely to result in "expected," affirmative answers than are nonleading, direct questions, such as "What kinds of grades does Jane get in school?"

Helping the Parent or Patient Communicate

Throughout the interview the parents or patient should be assisted in several ways to relate all necessary information fully. The practitioner should use medical terminology understood by the parents or patient. Words such as tinnitus, palpitation, and incontinence may have little meaning to the parents or patient, who often will be too embarrassed to ask for a definition and may simply answer "no" when asked if those signs and symptoms are present.

The interview process is one of interaction between the clinician and the parents or patient. The person providing information should do most of the talking and the practitioner most of the listening. However, the clinician can encourage the parents or patient to communicate their story by using the following seven techniques:

Facilitation. This is designed to convey interest in what the parent or patient is saying. Maintaining eye contact, leaning forward, nodding in affirmation, and saying "yes," "uh huh," "I see," and the like, all convey interest and encourage the parent or patient to continue. Additional information might be gained by giving an example, such as "In other situations like this, some parents have thought of alternative medicines. Have you thought so, too?"

Reflection. Repetition of words the parent or patient has said encourages him or her to provide more detail, as is demonstrated in the following example:

Parent: Kara woke up in the middle of the night breathing hard.

Interviewer: Breathing hard?

Parent: Yes, she seemed to be breathing fast and making a wheezing noise.

Interviewer: A wheezing noise?

Parent: Yes, in and out—a musical wheezing sound.

By using reflection, the interviewer was able to elicit the nature of the child's breathing difficulty without influencing its description or diverting the parent's thoughts.

Clarification. The interviewer often must clarify what the parent or patient has said; for example, "What do you mean by 'Rob wasn't acting right'?"

Empathy. Recognizing and responding to a parent's or patient's feelings of concern, fear, or embarrassment show understanding and acceptance and encourage continued expression of the emotion. "I can understand why that upset you" or "That must have been difficult to deal with" is an empathetic expression that tells the parent or patient that the clinician appreciates what he or she has been experiencing and is sympathetic. The practitioner also can ask the parent or patient how he or she feels or felt about a particular situation that has been related. This displays an interest in the parent's or patient's feelings as well as in the medical facts.

Confrontation. This technique is used to clarify what seems to be a contradiction between the parent's or patient's feelings and actions: "You say that Alison loves school but misses a lot because she has an upset stomach most mornings." Although confrontation is used to seek clarification, it also may lead to interpretation of the meaning of the contradiction.

Interpretation. This technique is used to move beyond clarification to an inference to be made from the circumstances presented. Thus, the above example might lead to the following statement and questions by the practitioner: "Maybe there is some relationship between Alison's upset stomach and her wanting or not wanting to go to school. Do you think that's possible?"

Recapitulation. This technique is especially useful when a long and complicated or an unusual history is presented. The clinician summarizes to the parent or patient the history as the clinician understands it. This may be done at more than one point during the interview and serves to confirm the validity of the history. It also allows for possible changes.

It sometimes is helpful toward the end of the interview to ask, "Is there anything else you think I should know?" This open-ended inquiry leaves parents with the sense that things were not rushed and that there is still room for discussion.

Hindrances to communication

Although a calm, reserved, interested demeanor is important to enhance communication, the practitioner must guard against appearing casual. Constant eye contact with the parent, interrupted by glances at the child (if present), should be maintained. Evidence of boredom or impatience—looking away from the parents or patient, tapping the fingers or a pencil on a tabletop, or rushing through the interview—must be avoided. Inappropriate smiling or laughter also hinders good communication. The parents or patient always should feel that they have the practitioner's undivided attention. If time is short, the parents or patient should be informed and another appointment made for completing the interview.

Interviewing the Child

A great deal of information can be gained by interviewing the child directly (see Chapter 79, Interviewing Children). Many children interact spontaneously with the pediatrician and answer direct questions readily. Often only the child can reveal the severity of the pain or the extent of the symptoms. Sometimes it is better to approach children indirectly, such as encouraging them to talk about their symptoms, than to seek direct answers. For example, "Tell me about your cold, Gordon" is preferable to "Do you cough?" The pediatrician should always support the child's "own story." It should be taken seriously, and confidences should not be violated except in unusual circumstances. With chronic problems, such as constipation or enuresis, it is helpful to review with patients their knowledge of the complaint. Patients can be asked what they were told before coming to the physician's office, how they feel about the visit, how their symptoms affect them and alter their lifestyle, and whether they are able to attend school and carry out all their regular activities. It also is important to ask children what they think is causing their symptoms, what they are worried about, and why it worries them. Interviewing the child provides another opportunity to assess parent-child interaction. Many parents cannot let their child speak without addition, interruption, or correction. A school-age child who clings to a parent and cannot be coaxed to make eye contact with the practitioner or interact in any way probably is overly shy and dependent. As adolescence approaches, parent-child conflicts become more intense. Given the chance, many adolescents will make this obvious. Under these circumstances, separate interviews probably are preferable (see Chapter 105, Interviewing Adolescents).

In many situations, information about a child's typical day can be very helpful and informative, and most parents can relate this information readily. In addition to concrete material (e.g., sleep patterns and feeding activities), much can be learned about areas of stress and harmony within a family. As with other aspects of the history, such information should be obtained as objectively as possible. Parents frequently find it difficult to discuss situations without seeking approval, even if tacit, of their own actions. Mothers who are confused or unsure of themselves frequently may ask advice on a particular aspect of their child's behavior as it is presented in the description of the child's typical day; however, it is best to defer answers until the entire day has been described. Discussion can begin with an introduction, such as "To find out more about Kim, I am going to ask you to tell me how she spends a typical day." The clinician should then begin by asking what time the patient arises and what happens. Some parents will launch into vivid descriptions and will require little direction, whereas others must be encouraged. Details can be elicited by asking some simple questions, such as "What is her mood on awakening?", "Who takes care of her?", and "What does she usually eat for breakfast?" Discussion can include food likes and dislikes, skill in eating, and conduct at the table. The practitioner also can learn about the child's activities, habits, and television viewing practices. The subject of discipline might come up during this discussion, and the parents' beliefs about prohibitions and punishments can be ascertained. Lunchtime, afternoon rest periods, and activities are reviewed in much the same way. Descriptions of trips to the market or to other stores can provide information about behavior with others and reactions to new experiences. The evening meal often is stressful in many families, and how it proceeds can provide many clues to family dynamics. For example, the clinician should find out when the parents arrive home, whether the child eats with the parents, and if so, the types of interactions that occur. Information about the events surrounding preparation for sleep, bedtime rituals, and sleeping patterns also is important. At the end of such an interview, it should be possible to assess not only the child's style and temperament but also the family's strengths and weaknesses. This information is essential for advising parents of children who are having developmental and maturational problems.

In certain instances, parental questionnaires may be used to supplement the history. Some may be used as part of a general health appraisal; others are more applicable to a specific problem. The Framingham Safety Survey is part of The Injury Prevention Program (TIPP) of the American Academy of Pediatrics. It is the basis of office counseling on injury prevention in child health supervision. Questionnaires are especially helpful for assessing school problems and developmental issues. The Denver Prescreening Developmental Questionnaire-Revised (R-PDQ) and the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBC) are but two examples (see Appendix D for more information about these questionnaires and others). The wise practitioner will be thoroughly familiar with the questionnaire format and its pitfalls before using it; all such instruments may supply additional information, but all also may be subject to observer bias and should be interpreted accordingly.

RECORDING HISTORICAL INFORMATION

There are two main goals in recording the historical data gained in an interview. First, the patient's symptoms and medical history, which will help in formulating a diagnosis and therapeutic plan, are documented. This serves as a legal record of the practitioner-patient encounter. Second, a reasonable account of the patient's medical status is made available to others who also are involved in the patient's care and to the person who initially gathered the information. The historical database should contain all the medically significant facts of the child's life. The recorded history is a synthesis of material and observations gained during the interview, compiled in a legible, retrievable form. The present illness must be recorded clearly and concisely. Consistency is paramount, especially when dealing with events in time. Events must be recorded by using either of these methods: "Dick developed a cough on March 17" or "Dick developed a cough 5 days before our interview on March 23." "Tuesdays" and "Fridays" are difficult to identify 2 weeks after an interview. Data obtained during an interview can be recorded in a variety of ways, ranging from tape-recording the entire session, a method often used by psychiatrists, to merely noting "Dx—acute otitis media; Rx—amoxicillin × 10 days" on an index card. Records should be legible, and much of the data should be retrievable without having to pore over volumes of paper. This requires some foresight and planning so that different parts of the history can be separated for later use. Ideally, the historical database should be standard and uniform. However, certain problems (hip clicks, birthmarks) change with time and vary by age and gender (menstrual irregularities), by type of population served, and by geographical locale.

A variety of questionnaires have been developed to facilitate development of the database. These are designed to be age appropriate and can be filled out by the parent or by a nurse, physician's assistant, or other office personnel. Such questionnaires can be used to gather a large amount of data quickly, thoroughly, and concisely. However, they also present several drawbacks. First, questions tend to be answered in an idealized way because parents usually have a skewed opinion of their children. Second, all logical sequencing of information gathering is lost, and degrees of concern are not readily expressed. Third, unless the database is updated frequently by subsequent questionnaires, much of the information soon becomes irrelevant.

Gathering and recording a history and communicating compassionately and courteously with patients and their families are difficult tasks. These are not innate skills but rather require work, insight, perseverance, and practice. The work is hard, but the rewards are great.

REFERENCE

Holt LE: The diseases of infancy and childhood, New York, 1908, Appleton-Century-Crofts.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Bickley LS, Hoekelman RA: Interviewing and the health history. In Bickley LS, Hoekelman, RA, editors: Bates' guide to physical examination and history taking, ed 7, Philadelphia, 1999, JB Lippincott. Cassell EJ: Talking with patients. In Clinical technique, vol 2, Cambridge, Mass, 1985, MIT Press. Feinstein AR: Clinical judgment, Baltimore, 1967, Williams & Wilkins. Klaus MH, Kennell JH: Parent-infant bonding, ed 2, St Louis, 1982, Mosby. Thornton SM, Frankenburg WK, editors: Child health care communications, Johnson & Johnson Pediatric Round Table No 8, 1983. Wessel MA: The prenatal pediatric visit, Pediatrics 32:826, 1963.

Copyright © 2001 by Mosby, Inc.

fourth edition

Editor-in-Chief

Robert A. Hoekelman, M.D.Professor and Chairman Emeritus, Department of Pediatrics University of Rochester, School of Medicine and Dentistry Rochester, New York